Bristol Harbour Railway – A Full History

The following covers the history and development of the Wapping (Bristol Harbour Railway) and Canon’s Marsh (Bristol Harbour Lines 1897) lines respectively.

In 1841 the Great Western Railway opened throughout between Paddington and Bristol, but it was not until 1872 that the city’s Floating Harbour had rail connected docks and wharves. On 11th March 1872 the Bristol Harbour Railway to Wapping Wharf opened for freight traffic. An expensive line to construct, because it was over developed land, it was owned jointly by the Bristol & Exeter and the Great Western Railway. Nearly thirty years were to elapse before more major railway works were constructed in the City Docks area.

In 1906 two new railway links were established under the Bristol Harbour Lines Act of 1897, and both were connected to the main Portishead branch at Ashton Gate. The first route left Ashton Junction signal box and, by means of a double track line, crossed the River Avon on the bottom deck of a new, hydraulically operated, double deck swing bridge. A single line then swung off this main line to run alongside the New Cut, this branch making an end-on junction with sidings of the Bristol Harbour Railway at Wapping Wharf.

The second branch ran on from the first at Ashton Swing Bridge North Junction. This important double track section crossed Cumberland Basin by yet another swing bridge and headed on to a large, newly constructed, goods depot at Canon’s Marsh. This was built on a site close to the city centre near the Cathedral.

The Bristol Harbour Railway (via Redcliff) was closed to traffic in January 1964, although a connection still remains (via Ashton Swing Bridge) into the Portishead branch at Ashton. One year later the Canon’s Marsh extension also closed.

In 1866, a Bill passed through Parliament allowing the construction, by the Bristol & Exeter and GWR companies in partnership with Bristol Corporation, of the Bristol Harbour Railway and Wharf Depot. To be precise, the corporation exercised their powers to construct the wharf itself, with a depot at that wharf, while the companies naturally built the connecting railway. The scheme was put forward in order to alleviate heavy road traffic through what were, even then, overcrowded city streets. Goods that were being transferred by road from the harbour, then still not rail connected to the main line companies’ tracks at Bristol, would be able to move directly from ship to rail, and vice versa, at dockside.

The cost of the scheme was estimated at £165,000 and was to be equally divided between the Bristol & Exeter, the G W R and the corporation, and considering that the line was only three quarters of a mile in length one can see just how expensive it actually was. It was engineered by Charles Richardson and work began in August 1868. Its construction forced the demolition of the old vicarage at the church of St. Mary Redcliffe, plus nearly all one side of Guinea Street. It involved the construction of a 282 yard long tunnel under the churchyard at Redcliff; for this the church received £2,500 in compensation. With the money received, some land, at Arno’s Vale in Brislington, was purchased and many bodies were reburied there. The railway gave access to a district that was generally poorly known to Bristolians. In laying out the line the surveyors had come across a considerable bed of `withies’ (which is a kind of willow particularly common on the Somerset levels) growing in the area between Redcliff church and the station at Temple Meads. In addition, much local interest was aroused by the (re)discovery of a comprehensive network of caves under Redcliff Hill during the line’s construction.

In 1869 the railway companies decided to increase the size of the wharfage provided for in the scheme. They applied for further Parliamentary powers while the corporation agreed to a 400ft. extension of the wharf, west of Princes Street Bridge.

The railway was opened on 11th March 1872 but not before the Inspecting Officer, Colonel Yolland, had examined it on 26th February 1872. Precise as ever, the report gives the following details of the line’s construction and route. According to the report the line was double throughout with the exception of the first 6’/z chains where the single line joined, end-on, a goods line of the Great Western Railway. The width of the line at formation level for the double line on the viaduct was 27 ft., on the embankment it was 30ft., while in the tunnel it was 27½ ft. In the two cuttings it was 29½ and 35ft. respectively. The line was broad gauge.

The permanent way consisted of flat bottomed Siemens steel. It was laid on cross sleepers of creosoted Baltic Redwood timber. The rails were secured to the cross sleepers by four 3/4in. fang bolts in each sleeper, except for the sleepers next to the joints which had six of these bolts. The ballast was of broken stone below and furnace ashes above. It was stated to be 11 in. deep. The sharpest curve on the line had a radius of 15 chains and the steepest gradient was 1 in 100.

There were five under and two over bridges in addition to an opening bridge over a lock connecting Bathurst Basin with the Floating Harbour. There was an arched viaduct 346 yards in length and a tunnel 282 yards in length. Four of the under bridges had brick abutments and wrought iron girders, while the other, and one of the over bridges and the viaduct and the tunnel, were brick built. The remaining over bridge was a footbridge at Guinea Street and was stated to be in place of a private level crossing. The wrought iron girders of the under bridges and of the drawbridge were regarded as being sufficiently strong.

Colonel Yolland thought that the whole of the works were very well executed and the line was in good order, but it was not intended, at that time, to be used for passenger traffic. Thus there were no passenger platforms or stations. The signalling was in an incomplete state and there were no connections between facing points and signals. He suggested a catch siding should be put in near the top of the 1 in 100 incline to prevent vehicles running backwards down the incline and across Guinea Street level crossing. One was warranted, he felt, connected with signals at the Manure Works siding! There was no lodge at Guinea Street crossing as the law required, and Yolland felt, that the gate should be moved by a lever at the side. In this way the keeper would not have to go into the middle of the road, a dangerous activity since there was a good deal of traffic using it.

One of the items particularly mentioned by Yolland in his report was the bascule bridge at Bathurst Basin. He suggested arrangements should be made for cutting off the supply of steam when the bridge was nearly horizontal or vertical. This the engineer, Mr Richardson, stated he would do. In fact, the bridge engine has had a very interesting history for, being removed on the line’s closure in the 1960s, it is now resident at the new industrial museum at Princes Wharf. A simple twin cylinder type, it was always kept in immaculate condition. Making about 110 r.p.m. to open or close the bridge, the latter was so well balanced that it needed roughly the same effort on the engine’s part to raise or lower the bridge.

In November 1888 a schooner carrying petrol blew up in Bathurst Basin, covering the waters of the Basin with flames. Under the extreme heat the bridge warped slightly. Operating the bridge was a little more complicated than at some of the other City Docks’ bridges, in that the bascule bridge was both a road and rail bridge while the water main supplying Wapping Goods Yard also ran across it, and this had to be disconnected. Two sets of gates and the operation of signals protecting rail traffic, all added to a more involved procedure. Interestingly enough, as late as 1961 an express goods from Temple Meads to Penzance, the 8.30 a.m. Down, was put down the Harbour Railway over the bridge.

Returning to Yolland’s report, he states that the line was to be worked with the assistance of the telegraph on the absolute block system, and that arrangements were being made similar to those then existing at Swansea Docks. The arrangement was such that electrical contact would be broken when the bridge was open and no telegraphic communication would be able to take place. In addition, Yolland suggested that the Up line, on the western side of the bridge, should have facing points running into a blind siding whenever the Up signals were at danger and, since there was a good deal of shunting going on in the G W goods yard at Temple Meads, Yolland also recommended that similar provision be made on the Down line there to prevent trucks being kicked over the top of the incline. These works were subsequently carried out. Yolland’s conclusion was that although he could not recommend the opening of the line to passengers, since the railway companies had no intention to prepare the line for passenger use, there was really no major stumbling block and so, on 11th March 1872, the Bristol Harbour Railway opened for freight business.

The line was an immediate success, so much so that in 1873 Parliamentary permission was obtained for further constructional work. This involved the building of two additional wharves, one on either side of Princes Street Bridge, while a third, over 1,400ft. in length, was built further down river at Wapping. The rail extension to Wapping was opened in June 1876 by which time the Harbour Railway had become the exclusive property of the G W R.

As we have read, and amazing as it is now to relate, it was not until the opening of the Harbour Railway that the City Docks in Bristol were actually connected to the main GWR network. This is particularly surprising when one considers that the G W R main line between Paddington and Temple Meads had opened some 31 years earlier on 30th June 1841. However, there had been high hopes of the docks becoming rail linked in 1863 when the Bristol & North Somerset Railway Company was incorporated with the aim of linking Bristol with Radstock. As part of the scheme, it was planned to construct a `dock tramway’ from Temple Meads down along the New Cut to a suggested quay on the south side of the Floating Harbour below Wapping. The line’s precise route was to have been on the north side of the Avon along Clarence Road terminating in the area beyond Wapping Road. (See map above).

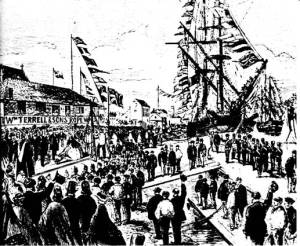

In spite of the fact that only around £16,000 of the £275,000 capital needed for the project had been subscribed at the time, work on the project began on 8th October 1863. On that date the Mayoress of Bristol, Mrs Sholto Vere Hare, `laid’ the first rail of the Dock Tramway. This is how the event was reported in the Illustrated London News of 17th October 1863.

“The first rail of the tramway connecting the North Somerset Railway with the Floating Harbour at Bristol was laid by the Mayoress, Mrs Sholto Vere Hare. The ceremony took place on a piece of ground on the towing path behind St. Raphael’s Church, where a platform had been erected for the accommodation of invited guests. The shipping was also well filled with spectators, and from Mr W. Terrell’s rope-walk to the edge of the water, with the exception of a small space reserved by the police, there was one dense mass of human beings. Rows of flags from various buildings, the rigging of vessels in the floating harbour, and, in fact, every salient point, imparted animation to the scene. The company was welcomed to the spot by the cheery strains of the artillery band and the merry peals of the bells of glorious old St. Mary Redcliffe. The work allotted to the Mayoress – which consisted of the filling of a highly ornamented barrow with earth, lifted with a silver spade, and wheeling it along a plank and overturning it – was efficiently performed, and was completed amid the applause of a large assemblage which the event had brought together. A large party afterwards adjourned to Mr Hyde’s sail loft, which had been decorated for the occasion, and where an elegant dejeuner was served, and several speeches delivered.

The silver ornamentations … on the barrow and spade (used by) the Mayoress of Bristol…. were the work of Messrs Mappin Brothers of London Bridge … Mrs Hare’s spade bears the crest of the Hare family, and underneath “Presented to Mrs Elizabeth Hare, Mayoress of Bristol, Oct 8, 1863”. To which is to be added, “In commemmoration of laying the first rail of the tramway of the Bristol & North Somerset Railway”

However, the company’s financial commitment proved to be overwhelming and some of the company’s directors were ruined. In 1869 the company obtained a new Act in order to finish the works but this was not to be and, in May 1871, the proposed tramway to the Floating Harbour, which even then was still unfinished, was abandoned.

In 1880 the Bristol Tramways Company applied for powers to construct tramways on the quays in connection with the Harbour Railway, but the city council, after initially approving of the plan, subsequently reversed its decision. Some development did take place, however, in the spring of 1888 when four more sidings were brought into use at Wapping Wharf. These sidings remain in use today at the coal concentration depot.

However, many interested parties still felt that the City Docks should be better served by rail and so, on 8th October 1889, the council approved an extension of the Harbour Railway to the Cumberland Basin, with sidings for the timber wharves and the Irish cattle trade, and an experimental coal tip at the Cabbage Gardens, Cumberland Basin. The estimated cost of the extension was to be over £10,000. It was agreed that a Bill should be promoted leaving final details to be made with the G W R while the Bill was actually in Parliament. In June 1890, Mr Charles Wills told the council that the Bill had passed one Parliamentary committee with little opposition. However, since the Bill was due to go before the next Parliamentary commitee in a few days time, and no arrangements had been agreed with the G W R, Mr Wills proposed that the Bill should be withdrawn. This the city council agreed to.

Mrs Hare, then Mayoress of Bristol, lays the first rail of the Bristol Harbour Tramway in connection with the construction of the Bristol & North Somerset Railway on 8th October 1863.

In 1892, at a council meeting on 11th October, the chairman of the Docks Committee, Alderman Low, pledged the council to promote a Bill for the construction of a similar railway to the one of 1890. This again had its route from the Bristol Harbour Railway down to the Cumberland Basin and then over a bridge across the Avon to the Portishead line. The Bill, however, never reached the statute books for, in the following year, the corporation did an about-turn on the issue. After the Bill had been introduced into Parliament, Alderman Proctor Baker, on holiday when the October meeting took place, returned to fight the new Bill tooth and nail.

At a special meeting on 20th June 1893 the council was called to decide whether or not the Bill should proceed. Due to some difficulties concerning aspects of the Bill relating to work at Avonmouth Dock, Alderman Baker then recommended that the section of the Act relating to Avonmouth should be withdrawn. This was agreed to. He then went on to say that the clauses relating to the Harbour Railway extension should also be withdrawn and this too was agreed. And so, in spite of popular support for the Avonmouth and Harbour Railway aspects of the Bill, nothing was done about these two projects.

On 27th September 1895, the council recommended the construction of a wharf over 1,500ft. in length from the Harbour Railway to the Cumberland Basin. The project was going to cost £120,000 and included £36,000 for the purchase of part of Messrs Hill’s premises. The G W R had also undertaken to give another £20,000 towards general improvements. The wharf was to be built essentially to aid the development of the timber traffic which, it was suggested, was leaving the port. The work included a railway from the Harbour Railway to the Portishead line, with a swing bridge over the Avon. This plan too was a non starter.

On 16th October of the same year the council met, yet again, to discuss the issue. Indeed, Alderman Baker, now chairman of the Docks Committee, put forward the proposal that the above mentioned wharf and railway scheme should be carried out. This plan was not agreed upon. It is very interesting to note, incidentally, the way that Proctor Baker put forward and supported a scheme that, only two years before, he himself had violently opposed! Two years was a short time in politics, even then!

The process to build the long overdue railway dragged on until, at a meeting in July 1896, Proctor Baker proposed that the 1895 plan should be turned into reality. This the council firmly agreed to do. However, at a statutory meeting of Bristol citizens, on 29th September 1896, the proposed Bill was rejected by a large majority! Eventually, however, under the Bristol Harbour Lines’ Act of 1897, the GWR obtained powers to connect the Bristol Harbour Railway with the Portishead branch.

Work began on this project in September 1897. Construction work centred on two sets of lines. The first of these left the Bristol Harbour Railway at Wapping Wharf and ran westwards parallel with the New Cut of the River Avon. It then curved southwards to cross the Avon by a new swing bridge, the Ashton Swing Bridge, before joining the Portishead branch at Ashton Junction signal box. (The second line, considered in much greater detail in chapter 10, left the Wapping branch near Ashton Swing Bridge, passed eastwards along the north side of the Floating Harbour to terminate in a new goods yard and depot at Canon’s Marsh).

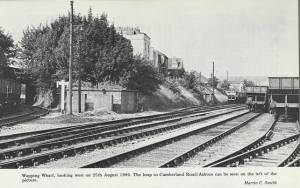

In detail, the line from the Harbour Railway ran for a distance of 53 chains between the New Cut of the River Avon and the Cumberland Road, the latter having been diverted in order to make room for the railway. Incidentally, roughly 20,000 cubic yards of soil were removed to `fit’ the line in between road and river, the majority of this spoil being used to fill in a portion of the former Merchants’ Dock which lay on the route of the Canon’s Marsh extension on the other side of the harbour.

Some interesting new bridges were constructed on the Wapping New Cut – Ashton Swing Bridge North signal box section. At 5 chains from the junction with the Harbour Railway, a new bridge was built to carry the Cumberland Road over the new railway. This bridge, with its skew span of 55ft., was built with a steel superstructure formed of two main girders and trough flooring. The abutments were of masonry and, owing to the nature of the ground, were built on 12 in. x 12 in. timber piles. A second bridge, very similar to this first one, carried a new road over the line near Ashton Swing Bridge itself. The Wapping Wharf New Cut -Ashton Swing Bridge North section was brought into use on Ath October 1906. Two months later, on 17th December 1906, the line connecting the corporation cattle pens at Cumberland Basin with the New Cut section was brought into action. This particular piece of railway bisected the main double track line of the Canon’s Marsh extension at Ashton Swing Bridge North signal box.

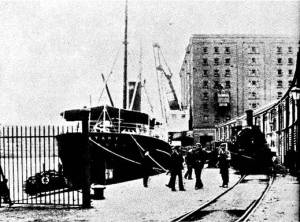

By 1908 the GWR had berthing rights for 1,600 ft. of quay served by the depot at Wapping, and a very extensive grain traffic from ship to rail was dealt with here. By this time the corporation had also erected a large granary adjoining the depot and in addition there were two spacious transit sheds. All were rail connected with the depot. There was a large mileage traffic, principally of coal, timber and flour, while as many as 350 wagons were occasionally loaded from the depot in one day.

Redcliff Yard was also a mileage depot which daily handled a large number of wagons. There was a large amount of flour and feeding cake traffic loaded at Redcliff from mills in the vicinity, while inwards a regular, and heavy, coal traffic was also dealt with. Once World War I came along, the Harbour lines were very busy with increased traffic in various commodities. Additionally, ships sunk by enemy action had to be replaced and Hill’s Albion Dockyard played its part in building wartime, “standard”, ships. The railways of the City Docks played their own part in carrying vital war supplies.

Post-war, in the early months of 1925, the signal box at Junction Lock was rebuilt, re-opening as a ground frame on 18th March 1925. At Avon Crescent, a new signal box had also been built and this was in a more favourable position in relation to the crossing and the various interlocking arrangements. This too was brought into use on 18th March 1925. More warehouses were built during 1929 at Wapping Wharf to deal with the traffic then being handled. In addition, in order to improve the tempo of working the goods traffic between Temple Meads and Wapping Wharf and Ashton Swing Bridge North signal box, electric train token working was installed during the latter half of 1929. This replaced the wooden train staff working previously in use. The new system was in operation by January 1930.

Midland Railway Depot, St. Philip’s, circa 1904, showing the wealth of traffic on tap. The view also shows one of the Midland Railway barges that plied between St. Philip’s and the City Docks.

An aerial view of the City Docks showing, from left to right, the line from Ashton Swing Bridge North curving around to the left, past Merchant Dock, along Hotwells Road and Mardyke Wharf, where two of Campbell’s paddle steamers can be seen. In the upper right hand corner of the photograph is the crowded wharf at Wapping. On the extreme right can be seen the Ashton Swing Bridge North to Wapping Wharf section running along the New Cut.

Two sections were necessary, namely Redcliff sidings to Bathurst Bridge and Wapping Wharf to Ashton Swing Bridge North. The Cumberland Basin ground frame, which had previously been locked by Annett’s Key, was now locked by token, as was Moredon siding.

Incidentally, one of the incentives for the GWR to substitute electric train token working along the New Cut may have been the future and foreseeable use of the route as a diversion, while work was taking place on the main line in connection with the 1930s quadrupling between Filton Junction and Portishead Junction. In the following year additional siding room and other accommodation was provided for the coal traffic at Wapping Wharf. These were, indeed, busy days.

One of the railwaymen working both Portishead and City Docks lines in the 1930s was the late William James R. Pollard. After being a telegraphist (Booking Boy) at Bristol East signal box, he started as a Grade 2 porter at Pill on 29th August 1927 at the age of 20. During his time at Pill he applied for promotion several times but for some reason was never successful. One day, whilst he was cleaning and tidying up the stationmaster’s office, he pulled out a drawer and found, to his surprise, all his applications neatly bundled inside – they had never been sent off! The next time he applied for promotion, the application was sent directly to Bristol, thus by-passing the stationmaster. Shortly afterwards an Inspector got off a Down train and demanded, from Mr Pollard, an explanation, which was duly given. It later came about that the stationmaster received a private rebuke!

Promotion came by the normal channels and, on 3rd July 1930, William Pollard started as a porter/signalman at Pensford. He returned to Bristol on 8th August 1931 as a Class 5 Goods signalman at West Depot/Swing Bridge North. (According to his notebook he was learning on the 8th, appointed on the 12th and `on nights’ on the 13th! Interestingly, only the 8th August appears on his staff record). While working at Swing Bridge North the following incident occurred. Mr Pollard had a Down train `on line’ from Ashton Junction to Wapping and had been offered an Up goods from Avon Crescent which he could not accept. Then came an urgent phone call from Avon Crescent; could he accept and give the road to the Up goods as there was a ship under way down the harbour and the Up goods was standing on Juncton Lock Swing Bridge? No doubt urged on by the thought of the ship colliding with the bridge, William Pollard returned the boards to normal behind the Down goods. He then pulled over the Down facing points for the Canon’s Marsh line in order to release the Up trailing points. However, he was a second too soon, for the rear wheels of the brake van just caught the ends of the point blades as they moved across and they derailed. As the couplings of the goods grew taut around the curve towards Wapping, so all the wagons came off the road. However, at Avon Crescent, they had solved their dilemma by splitting the train, leaving the rear portion on the Canon’s Marsh side, the forward portion drawing clear on to the Avon Crescent side. Very soon after, an Inspector arrived to question Mr Pollard about the incident, but as far as Mr Pollard’s son is aware no disciplinary action was taken.

During the 1930-35 period engineering work on the main line brought passenger trains on to the Ashton-Wapping line. Indeed, this practice continued after this time when, for example, during World War II, bombing near the signal box at Bedminster, on the Temple Meads-Parson Street Junction section, blocked the main line for between 12 and 24 hours on 3rd January 1941. Once again in the Bristol Harbour Lines’ history, passenger trains were seen traversing City Docks’ metals. Mr Pollard eventually left Swing Bridge North and moved to Filton West signal box, where he started on 11th March 1935.

Leading on from what was said in the last paragraph, the traffic from the Canon’s Marsh and Wapping areas was immense during World War II with pilots on duty 24 hours a day at both places. At those times when convoys were in dock, trains were formed at Ashton Meadows through to destination. There was no remarshalling etc. for these trains within the Bristol area, this practice ensuring the rapid clearance of these vital freights from the City Docks.

Bristol had to put up with occasional bombing attacks throughout the summer of 1940. However, the real blow fell on 24th November when the City Docks area was badly damaged and 200 people died. Charles Hill’s shipyard was hit, as it was, yet again, in the next major raid on 2nd December 1940.

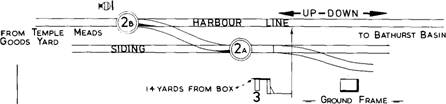

REDCLIFFE GOODS YARD

G.W.R. SIGNAL ENGINEER’S OFFICE READING.

One incident during the war, recorded by D. J. Fleming in his railway reminiscences, concerned the Redcliff pilot. On this particular working, the small signal box at Redcliff was generally used for shelter when bombing became particularly bad. One night when bombing took place, the shunter had a brake van pushed inside Redcliff Tunnel for greater protection. Coincidentally, the box was hit that night and after that the tunnel, like others in the area, became regularly used as an air raid shelter. Once the war was over, port and railway activities soon returned to normal at Wapping and Canon’s Marsh.

`To the returning servicemen in 1945, the Port of Bristol seemed much the same as the one they had left six years before. The busy selfconfident life of the docks was vibrant as ever. Coasters called in at the City Docks again, and cargoes came and went as before from Princes Wharf, Canon’s Marsh and Wapping. The Scandinavian timber boats were back at Baltic Wharf and joy of joys, the Rauenswood took Campbell’s first post-war excursion out of Hotwells . . . Albion Dockyard was busy with new orders … Typical were a Trinity House light and buoy, a light-ship for Ireland, numerous dredging craft … and a variety of tugs’.Text: F. Shipsides and R. Wall

The late 1940s and the decade of the 1950s were good years for the City Docks and before closure to commercial shipping, Wapping Wharf handled a variety of traffic including coal, esparto grass, wood and alcoholic beverages such as sherry and Guinness. The latter would come in on Guinness boats such as Juno and Cato, while another common cargo was sherry. Sometimes casks in transit would `spring’ or split and workers in the vicinity might go home that day with a little `unofficial’ sherry to their name. Meat traffic was also handled. For example, on Sunday evenings there would be railway meat specials to London. These trains, often hauled by 49XX `Hall’ Class engines, would be loaded with produce brought in by the meat boats which were also a regular sight in the City Docks.

The late 1950s produced two rather interesting railtours of the City Docks area. The first took place in 1957 when the RCTS organized a tour from Paddington to branch lines in the Bristol area. The tour had Class N15, No. 30453 King Arthur at its head from Waterloo to Reading. Here No. 3440 City of Truro took over for the leg, via Trowbridge, to Bristol. Ivatt 2-6-2 tanks Nos. 41202 and 41203 took the special over the dock lines along the New Cut to Ashton Junction, West Loop North Junction and the former G W R main line west to Wrington, Highbridge and Burnham. The special then returned to Bristol where No. 3440, ably assisted by 55XX class No. 5528 from Bristol to Westbury via Radstock, took the train back to Paddington.

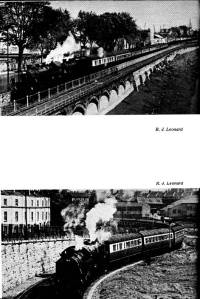

Ex-LMS 2-6-2 tank engines, Nos. 41202 and 41203 haul an RCTS special on the Bristol Harbour Line on 28th April 1957

In 1959, on Sunday 26th September to be exact, another special covered several of the goods only lines in the Bristol area. The three coach special, headed by an ex-works condition panner tank, No. 9769, visited Wapping Wharf, Canon’s Marsh, Avonmouth, Yate and the branch to Thornbury. New ground was broken by the special’s visit to Canon’s Marsh goods depot. The coaches used were 57ft. in length and great care had to be taken on the severe curves near Cumberland Basin Swing Bridge. The buffers almost locked in places, the railway staff having to loosen couplings for the sake of safety as well as ensuring that all points on the route were clamped.

On more ordinary, everyday, workings an interesting run was to be had on the single line from Temple Meads to Wapping Wharf through Redcliff Tunnel. Ron Gardner, a former G W R and BR (WR) driver, clearly remembers driving freights out over Victoria Street Bridge, past the yard at Redcliff goods to the General Hospital and Guinea Street. Trains would rumble on over the bascule bridge, which frequently caused delays, eventually reaching the level crossing at Prince Street and the Wharf at Wapping. Memories of the shunting staff in the line’s later days, Joe Marton, `Tiger’ Lewis and Bill Rowlands, soon come drifting back!

There were complaints on many occasions from people living around Wapping because of noisy shunting at night and early in the morning. Ron believes that the complaints came mainly from the (then) vicar of St. Raphael’s Church who lived in the nearby vicarage! The train most responsible for these complaints was the 5.40a.m. transfer from Temple Meads to West Depot (via Wapping). Now, like the 23XX standard goods locomotives that used to haul these trains, the line under Redcliff and the extension to Canon’s Marsh have gone. Indeed, with the 1960s came the run down of the City Docks and the beginnings of the decline and fall of the Bristol Harbour Railway.

From 1960 onwards the rot truly set in. In December 1960 the line over the Victoria Street Bridge was singled while two years later the once busy yard at Redcliff goods was closed on 1st June 1962. The entire line from Temple Meads Goods Yard to Prince Street was closed completely on 11th January 1964. Subsequently the closed section was lifted from Prince Street back to Temple Meads and today, with the major exception of Redcliff Tunnel, the alignment has all but disappeared under a new hotel, a road flyover and various industrial and commercial premises. Further removals took place at the Ashton end of Wapping Wharf in November 1966 when the siding to the timber firm of Wickham & Norris was closed.

However, all was not lost! Wapping Wharf was still served from the Ashton end.Until 1987 there was one daily coal train to Ashton Meadows sidings where a private owner locomotive from Western Fuels Limited took the train along the New Cut to the coal concentration depot at Wapping Wharf. The locomotive normally involved in this working is the company’s Hudswell Clarke diesel-mechanical 0-6-0 shunter, No. D1171, built in 1959. It was formerly used at both PBA Avonmouth and Portishead until Western Fuels Limited purchased it for their own use.

In the later days of steam haulage, most of the workings on the City Docks’ lines were handled by ex-GWR 0-6-0 pannier tanks. In early diesel days, 0-6-0, Class D9500 diesel-hydraulic shunters often shunted the coal trains. These were supplemented by 0-6-0 diesel-electrics, Class 08, but larger diesels such as `Westerns’, `Peaks’ and `Hymeks’ were often seen on coal trains. As for traffic on the Ashton Junction/Wapping line in its later years there was still some variety.

An RCTS special, hauled by Nos. 41202 and 41203 rounds the sharp curve leading from the Wapping line on to the main Canon’s Marsh line at Ashton Swing Bridge North. This train had been hauled by ex-SR 4-6-0, No. 30453, King Arthur from Waterloo to Reading, where ex-GWR, No. 3440 City of Truro had taken over for the Reading to Bristol, via Trowbridge, leg. Nos. 41202 and 41203 had handled the trip over the City Docks lines in the Bristol area. City of Truro hauled the train back to Paddington, with assistance from ex-GWR `4575′ class, No. 5528, between Bristol and Westbury, via Radstock. The trip was organized by the RCTS and ran on 28th April 1957.

Wapping Wharf and Canon’s Marsh in their heyday. Note the large number of railway wagons at Wapping and the timber being unloaded into barges for delivery to paper and cardboard mills further up the river. During World War II, the harbour lines were very busy indeed. When bombing raids occurred, all swing bridges were swung open in order to minimise damage to them. All trains came, to a halt, the crews staying with their engines.

Below is reproduced a typical Monday working during the September 1975 and July 1976 period as seen by Paul Holley. `Around 8.00 a.m. a coal train, made up of both 21 and 24 ton wagons, would arrive with coal for Western Fuels Depot at Prince Street. The engine would deposit the train at Ashton Meadows, run round and leave the branch light. After waiting some time at the level crossing at Ashton Junction, it would then proceed towards Parson Street around 8.50 a.m./8.55 a.m. Shortly afterwards, (the times varied) a diesel shunter would arrive. This would haul the full coal train to Whapping Wharf coal depot where it would do some shunting. It would return with the empties which it would leave in the sidings at Ashton Meadows. Shunting engines were sometimes seen leaving the branch as late as 4.30p.m.’

`Later in the morning, often just after 10.30a.m., a works train for BR’s civil engineering depot at Ashton Gate would arrive and leisurely shunt an odd mixture of antiquated rolling stock in the sidings. After having formed a train with stock from the B R depot the train would depart, usually between 12.15 p.m. and 12.45 p.m. Sometimes departure was not before 1.30p.m. and, exceptionally, much later if the morning arrival was late. At about 11.OOa.m./ 11.15a.m. a train of woodpulp empties for Portishead Dock would pass through Ashton Junction. There would be a short stop at the temporary level crossing used for contractors’ vehicles working on the flood alleviation scheme, near the headquarters of the Mounted Police. Incidentally, the latter had, by now, been built on the site of Clifton Bridge Station. The driver would open the gates for the train to proceed. By about 12.10 p.m. it would have returned loaded with woodpulp. It would wait alongside the Clanage playing field for the crossing gates to open and by 12.20 p.m. the train would proceed to St. Anne’s Board Mill.’

`On rare occasions a short freight, made up of cement wagons bound for Portishead, would pass through Ashton Junction at around 12.30p.m. while during the afternoon, usually between 2.30 p.m. and 3.30 p.m., another coal working would often run. Occasionally, a light engine would arrive, but more often than not this was usually a loaded coal train. Whereas the morning train might consist of up to 50 hopper wagons, the afternoon train often had fewer than 20 wagons, often 16 ton mineral, and on one occasion, Paul remembers only six in the train. The locomotive would then depart with the empties more often than not, although he can remember that once or twice there were full coal wagons in the train! Departure was around 3.30p.m./ 4.OOp.m., sometimes later. Often as late as 4.30p.m. the pulp train would return empty from St. Anne’s to Portishead for the second working of the day. It would return again around 5.30p.m. and the same locomotive would handle both the day’s workings. Very occasionally, cement hoppers would be worked with the woodpulp wagons’.

Ex-GWR 0-6-0 pannier tank, No. 9729, swings around the curve near Ashton Swing Bridge North signal box and heads towards Wapping along the New Cut with a freight train in 1960.

The lines to Wapping and Canon’s Marsh were, generally speaking, both well used. The City Docks were always busy with such traffic as the Guinness boats from Dublin and the esparto grass boats from Spain and North Africa. This particular grass was used for making bank notes at a paper mill near Wookey Station on the line from Yatton to Witham, the Cheddar Valley line. Special trains were run carrying this grass and they were known to railwaymen in the local area as the `Wapping and Wookey Specials’. These would leave Wapping Wharf, travel to Ashton Meadows and then on to the G W R main line to the West Country at West Loop North Junction. They would then travel on down the main line, the esparto grass being unloaded from ship to rail in the City Docks to Yatton where they would join the Cheddar Valley line for their journey to Wookey.

`During this period Tuesdays and Wednesdays were normally quieter, with coal and woodpulp workings only. On Thursdays a short freight for Portishead would pass through Ashton Junction at about 11.15 a.m. This usually consisted of four to seven Presflo wagons, and sometimes mineral wagons and box vans were included. This train later appeared more often on Fridays, often early in the afternoon. The return works train for the BR depot at Ashton Gate also ran on Fridays. Other workings during this period included rakes of empty wagons for storage at Portishead and road salt trains, the latter often being stored in a siding near the SS Great Britain. By late 1976 only one woodpulp train per day ran. By early 1977 the workings had become sparse and erratic and soon they ceased completely. During the summer of 1977 some 26 of the woodpulp wagons were stored at Ashton Gate alongside the Clanage.’

By 1980, although the coal workings continued, the shunting was now handled by Western Pride, the engine belonging to the Western Fuels Company. Portishead freight workings, basically cement, were far fewer and were handled, generally speaking, by Class 31 locomotives. Wagons, including new Railfreight vans, sometimes appeared at Portishead, presumably being in storage there. Occasional road grit trains still appeared and the works trains still continued in the Ashton area.

In the autumn of 1981 the ex-PBA 0-6-0 shunter Henbury (Peckett 1940) successfully completed a three week contract hauling 450 tonne loaded coal trains from Ashton Meadows to Wapping Wharf. The locomotive, preserved by the Bristol Magpies, a steam preservation group attached to the Bristol Industrial Museum, had received a full overhaul in the Port Authority’s locomotive sheds at Avonmouth the previous winter. Once the 3 week contract expired another PBA locomotive, this time Rolls-Royce Sentinel No. 41 (10220), replaced the steam locomotive. Both engines were required as replacements while the firm’s own locomotive was being overhauled.

Further activity occurred, in July 1981, on the Wapping/Ashton Junction section, when a serious collapse occurred on part of the Cumberland Road which had slipped into the New Cut. City of Bristol engineers had to relay track ballast on the Wapping line since, at one stage, the track was left suspended in mid air after the landslip. However, after a good deal of work by the City Council’s engineers and PBA staff, the line was subsequently reinstated. Until 1997, Wapping Wharf remained linked to the main B R system by a spider’s thread of a connection, the last remaining section of railway to reflect on in the City Docks.

`Strangely enough, the G W R, whose foundation in the 1830s was conceived in Bristol, rarely showed any initiative to develop the port trade by rail facilities in the closing decades of the nineteenth century. They were virtually local monopolists and concerned to keep the MR from too close contact with any of Bristol’s docks. Monopoly men wear leather suits.’

Text: W. G. Neale

In 1888 a Bill was introduced to put into effect a plan for connecting the Port & Pier line at Hotwells with the area around Canon’s Marsh. It was not a new idea and the difficulty and expense of joining the district around Canon’s Marsh to the railway systems to the east and south of the city had, for years, led people to think of the Port & Pier as the means to do this. The new line would have started from the Port & Pier Station at Hotwells and, after running through the rocks, along the back of St. Vincent’s Parade, it would have emerged in Clifton Vale near Cornwallis Crescent, where there was to have been a station. It would then have continued underneath Clifton Wood, Jacob’s Wells and Brandon Street emerging into College Street. There would have been a terminus on the site of Green’s Dock which was almost exactly where the goods shed was finally built at Canon’s Marsh in 1906. There would also have been branch lines to the gasworks and the, then, new wharf, both at Canon’s Marsh. From there the line would have crossed the Floating Harbour, by means of a swing bridge, to the Grove and Welsh Back. This scheme came before Bristol Chamber of Commerce. In principle, it approved of the line but felt that certain sections of it should be under the control of the city council. This view was put forward to the council and the House of Commons. Indeed, they also sent a deputation to the directors of the Midland Railway urging them to support the project. It was, however, all in vain and nothing further was done.

In 1890, when the Port & Pier came into the joint possession of the G W R and the MR, people again began to ask if something could be done to connect it with the City Docks. The Chamber of Commerce encouraged both railway companies to support the scheme which was then being revived. Success looked more likely and the Midland Railway drew up the notice of its intention to apply for Parliamentary powers. The line was included in the Omnibus Bill then being promoted by the company.

This new scheme would also have started at Hotwells Station. It would have terminated on the eastern side of the Butts, opposite the then George Hotel, near today’s Exhibition Centre at Canon’s Marsh. The General Manager of the Midland Railway wrote to the Secretary of the Chamber of Commerce, on 17th November 1891, saying that the directors of the company intended to go ahead with the line. Later that same year, however, the Midland directors then declared that they were not prepared to take on a project involving so much capital expenditure. It was found, for example, that the amount of tunnelling involved would have pushed the total sum needed to build the line up to around £400,000 and so the proposal was reluctantly abandoned. In addition, a number of private citizens put forward a plan to build railway facilities to the north side of the Floating Harbour and to connect them, again by means of a tunnel, to the CER at Montpelier Station but once again the cost was found to be prohibitive.

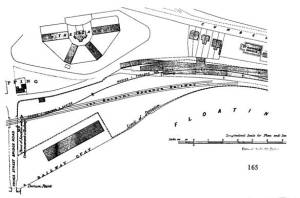

A plan showing the proposed route of the railway from the Port & Pier Railway to the Grove : 1888 Act.

RAILWAY No 3.

In 1892, the Chamber of Commerce again urged the Midland Railway to take action. They reasoned that the Bill that had been previously dropped, tacitly admitted the need for a rail connection to the north side of the harbour and that the construction of deep water berths at Canon’s Marsh had increased the need for a railway connection. The Midland Railway promised to keep the matter in mind and, to make sure that they did, a large deputation of Bristol citizens saw the directors in November 1892. Again the company was favourably disposed to the plan and agreed to issue Parliamentary notices. The preparations for applying the Bill to authorize the line from the Port & Pier to Canon’s Marsh were entered into. The project looked distinctly hopeful but, unfortunately, the matter was again dropped.

Yet again the Chamber of Commerce wrote to the Midland Railway, but to no avail. In order to maintain the momentum of the campaign to build a line, Mr (later Sir) George White laid before the city a plan to construct a line from the Port & Pier to Canon’s Marsh with a station at Cumberland Basin. The scheme, prepared in September 1892, allowed for an extension from Hotwells Station avoiding most of the tunnelling put forward in the other proposals. The cost was to be around £140,000 but when the scheme was put to the Midland, it was rejected.

It seemed as if Canon’s and Deans Marsh wharves would never be rail connected either with the Great Western or the Midland railways. The city council continued the struggle and they put forward plans, in 1892, for extending the Harbour Railway. This extension would have served the timber yards on the south side of the Floating Harbour, the line continuing down Cumberland Road and on across the Avon to join up with the Portishead branch across Ashton Fields. However, this line was not built after a strange turn around in council policy in 1893. The route to Canon’s Marsh was tortuous but gradually history shows the build up to the route finally chosen.

In December 1895, the Chamber of Commerce once more intervened. It petitioned for a railway following almost exactly the route later adopted in 1896. This ran via the Cabbage Garden, Cumberland Basin, across various bridges over various locks, past the Merchants’ Dock, Mardyke Wharf and then on to Canon’s Marsh. In 1897, the G W R finally co-operated with the corporation in the building of a goods depot at Canon’s Marsh. This was finished in the autumn of 1906. After all this preparatory work it seems ironic that considering the involvement, from the late 1880s onwards, of the Midland Railway, the construction of the line to Canon’s Marsh was finally carried out by the GWR.

All these plans and proposals suggest that the area around Canon’s Marsh was rich in traffic potential for the railways. The reverse was, in fact, the case. Canon’s Marsh itself was, at one time, Cathedral property and consisted of marshy meadows stretching from the precincts of the Cathedral down to the Avon, which later became part of the Floating Harbour. Before the railway came there was very little here; a gasworks, a marble and slate works, a few timber yards; so why did the GWR decide to build an expensive line to this fairly quiet part of Bristol right on the doorstep of the city centre?

The main aims of the project were as follows:

1) to give, for the first time, rail access to the deep water wharves on the north side of the Floating Harbour

2) to develop the advantages of Canon’s Marsh as an industrial part of the city

3) and, by dealing with all West of England general goods at the new Canon’s Marsh Depot, to relieve the congestion of traffic at other important goods stations, for example Temple Meads and Pylle Hill

On the branch to the new depot it was necessary to support the line alongside the Floating Harbour by constructing a retaining wall 500 ft. in length, and of an average thickness of 10 ft., built in concrete and faced with brick above water level. Beyond this was Mardyke Wharf, where provision had been made for unloading goods direct from ship to rail. The length of the wharf and the adjoining St. Jacob’s Well Wharf was 19 chains. Ten chains further on was the entrance to the `piece de resistance’, the new goods depot itself, an impressive building served by an impressive yard of no less than 320 chains of sidings.

The shed was built of reinforced concrete on the Hennebique principle. It had warehouses, offices and the shed proper. The warehouse was 270 ft. long by 133 ft. wide, was 35 ft. in height and contained a floor area of over 35,000 sq. ft. There were two platforms 20ft. wide running the entire length, and on these were eight cranes and three hoists all electrically operated. Four lines of track ran through the shed. The contractor for the building was Mr Robertson of Bristol, while the work was carried out under the supervision of Mr P. E. Culverhouse, architectural assistant to the new works engineer.

In connection with the new railway works at-Canon’s Marsh was the associated work carried out under the 1897 Bristol Corporation Docks Act. Under this Act the corporation increased the deep water wharfage at Canon’s Marsh by 935ft., making a total length of over 2,500ft. They also laid railways around the quays at Canon’s Marsh and these connected with the new GWR lines. The corporation also built two new transit sheds, one being 275 ft. by 113 ft., the other slightly smaller at 200 ft. by 93 ft. Both were double storied and were equipped for the most up to date and efficient transhipment of cargoes.

One notable result of the Canon’s Marsh extension was to give the Bristol Gasworks at Canon’s Marsh direct rail communication with the company’s principal plant. It also provided direct rail access to the two tobacco warehouses which were then being constructed, by the corporation, close to the swing bridge over the Avon at the Cumberland Basin end of the Floating Harbour. One of these warehouses was 300 ft. by 100 ft. and had six floors, the other being 200 ft. by 100 ft. with nine floors. Close by were the lairage, cattle pens and sidings which had been provided chiefly for the Irish traffic. With the new developments the Cork and Waterford steamers were able to discharge their livestock within a few yards of these, thus avoiding a drive of one or two miles to the nearest railhead. Cumberland Basin and New Junction lock were both spanned by steel bridges, the latter being a swing bridge worked by hydraulic power.

Further description needs to be given of the Ashton Swing Bridge. This structure, built by Bristol Corporation, was unique in construction and controversial in cost. The bridge had originally been estimated to cost £36,500 and the GWR had agreed to contribute roughly a half share (£18,000 to be precise). In fact, the bridge eventually cost over £70,000 and, since the GWR had agreed to pay half, there was a good deal of public outcry when the true cost was revealed, especially as the G W R’s contribution was specifically mentioned as £1$,000 in the Act. The Docks Committee was accused of bungling the whole issue. Apparently the additional cost had been engendered by alterations to the location and construction of the bridge, while the Docks Committee had felt it undesirable to make the G W R pay a larger contribution because the committee were very keen to see Canon’s Marsh rail connected. However, when work was completed, pressure was put on the G W R to contribute a larger sum to the cost of the bridge. This they did, £22,000 being the sum agreed and this was in spite of the fact that the Canon’s Marsh railway project had cost the GWR £130,000 more than had been originally estimated.

THE WORKINGS OF ASHTON SWING BRIDGE

`. . . When the bridge-master wishes to swing the bridge for rivertraffic, he rings, from the machinery-tower, a bell in each of the railway signal cabins, and as soon as the signalmen have withdrawn their bolts he receives a reply signal. The withdrawal of the railway bolts mechanically releases the lever by which the bridge bolts are actuated, and he withdraws these bolts. This movement back locks the railway bolts and electrically releases the lifting-press lever, which he then pushes over; and as soon as the ends of the bridge are lifted correctly, the slidinglock lever is electrically fixed. When the sliding blocks are properly withdrawn, the ends of the bridge can be lowered and the action of lowering frees the starting valve handle, enabling the bridge to be swung open. When the bridge has been turned to its open position, one of the screens can be raised by means of a lever to obscure the red light for one direction only.

In order to close the bridge the screen must first be lowered so that the red light is again shown; then the bridge is turned to the railway position and the shooting of the automatic locking-bolts electrically frees the lifting-press lever; this lever is then pushed over, and the lifting of the ends of the bridge frees the sliding-block lever; the sliding blocks are then inserted and the lifting-press lever is pulled over to lower the ends of the bridge; this electrically releases the interlocking-bolt lever which is moved over, thus electrically locking the turning, slidingblock, and lifting-press levers, and mechanically releasing the railway bolts, which being shot put an electric lock on the interlocking lever.

Electric indicators fixed in the machinery-tower give the following information to the bridge-master.

1. Railway bolt : shot or withdrawn

2. Lifting-presses : up or down

3. Sliding blocks : in or out

4. Automatic locking-bolt : shot or withdrawn

5. Bridge set for road or river

Of the first four indicators, there are two sets, one for the nose end and the other for the rear end . . .’

Text: Savile in ‘Swing-Bridge over River Avon’ Inst. C.E. Vol. CLXX

The bridge, along with the rest of the Canon’s Marsh/Wapping scheme, was opened for traffic on Thursday, 4th October 1906, by the Mayoress, Mrs A. J. Smith. The length of the bridge was 582 ft. and it contained 1,500 tons of steel in its original condition. Opened and closed by hydraulic power, it was worked from a central control tower, the swinging portion of the structure weighing 1,000 tons and being 202 ft. in length. Bristol made, the bridge was built by John Lysaght & Co.

The river traffic, for which the bridge was designed to swing, consisted, for the most part, of small coasting vessels and barges which, at that time, entered the docks via Bathurst Lock and Basin. Larger vessels used the deeper lock at Cumberland Basin and, even at its time of construction, there was some doubt as to whether there was any real need for a `swinging’ bridge at Ashton. Indeed, by 1912, it had been discovered that the decline of traffic up the New Cut meant that the Ashton and Vauxhall swing bridges did not really justify their being kept as opening bridges. However, there were problems in closing them and although the matter came up from time to time, it was not until the 1930’s that the Ashton Swing Bridge was finally swung for commercial traffic, 3rd February 1934 being the exact date of this event. The bridge was eventually made a fixed bridge under the 1951 Bristol Corporation Act. The control cabin and top road deck were removed as part of a comprehensive road and bridge rebuilding scheme that was completed in 1965 at a cost of over £2½ million.

Returning to 1906, and the construction of the line between Ashton Swing Bridge and Ashton Junction, the route passed through Ashton Meadows and here siding accommodation had been provided for the storage of wagons en route to and from Canon’s Marsh. Near the junction of the new line and the Portishead branch a bridge, carrying the former Ashton Road over the railway, had been constructed in order to give clearance for the additional tracks of the Canon’s Marsh/Wapping lines. Once under this bridge the new tracks joined the old at Ashton Junction signal box, which was opened 20th May 1906. Incidentally, the branch to Canon’s Marsh had other signal boxes at Ashton Swing Bridge South, Ashton Swing Bridge North (junction for the Wapping line) Avon Crescent, Junction Lock and Canon’s Marsh.

Before leaving the new works altogether, we need to mention the new construction work that had been taking place at West Depot, on the G W R main line to Weston-super-Mare, near Portishead Junction. Here extensive siding accommodation had been provided along with two relief lines laid in for a distance of 63 chains. A double track connecting loop had also been laid in from the Exeter direction joining the Portishead branch at West Loop North Junction. The Up relief line was brought into use on 8th April 1906, the Down relief on 6th May 1906 while the West Loop curve itself came into use on 4th October 1906 along with all the other Bristol lines’ works. All of these works were designed and carried out under the supervision of Mr W. Y. Armstrong, the new works engineer for the GWR. The contractor for the portion of the line from Merchants’ Dock to Canon’s Marsh, including the new depot, was Mr Strachan of Cardiff. The rest of the work was carried out by Messrs Nuttall of Manchester.

The Bristol lines soon settled into efficient operation. One way that this had been achieved was the fact that the Inspector in charge at Wapping and Canon’s Marsh was made directly responsible for the supply and berthing of empty wagons. He alone was responsible for the working away of traffic and this helped to facilitiate traffic working generally. One interesting point to note here was that the Inspector on the Harbour line was supplied with a uniform trimmed with gold braid. The reason for the admirallike uniform was that the GWR considered it gave the Inspector greater authority over the dockmen. By all accounts, there had been few delays over the various swing bridges during the first year of operation and the corporation had co-operated fully with the GWR in moving the traffic on offer.

Early in 1924 authorization was given to improvements in the lifting appliances then in existence at Canon’s Marsh. The scheme consisted of the extension of two of the existing electric platform cranes, in order to get a greater height of lift when dealing with bulky loads. A 30 ton electric gantry crane was to be provided in the yard to replace a 12 ton fixed crane then in use. The new electric cranes were brought into use by January 1926.

A former GWR and BR (WR) man, Ivor Phillips, reflects upon his experiences as fireman and later as driver in the Canon’s Marsh area from the late 1930s onwards. He remembers when Canon’s Marsh Goods Yard handled beer, imported Guinness, imported steel and crated general goods and cargo. The yard itself was partly surrounded by an iron fence. Approaching the goods yard from the city centre, one came across a pair of gates at the bottom of Canon’s Road and these led into the yard. First you passed the goods shed and just beyond this building was the shunter’s cabin. This was long and narrow, one half of it being reserved for the foreman and the other for the shunters. The iron fence mentioned above ran up the right hand side of the yard and on the other side of this fence was Anchor Road and beyond this was the Cathedral back. The fence also ran along the bottom of the yard to another set of gates. These led out on to the City Docks and were locked when not in use. On the left hand side looping up the yard was one wall of a large tobacco warehouse. This wall enclosed the yard on that side.

At the top of the yard was a crossing leading from Anchor Road to Gas Ferry Road. This, naturally enough, led on to the ferry which plied across the Floating Harbour. It was a dangerous crossing because so many people used it. There were lorries going to the gasworks, seamen going to their ships and people on their way to the ferry. There was a signal box at this crossing called Canon’s Marsh signal box and this controlled two banner signals, one for trains going out of the yard and the other for trains going in. The small levers operating these signals were about 1 ft. in length.

The remarkable thing about Canon’s Marsh box was its size. It was only about 12 ft. long and 4 ft. wide. Indeed, it was so small that two men could not pass one another inside without turning sideways. Many spent years of their working lives in such a confined space. The staff had to be very accustomed to trains for wagons passed very close by and there was very little room to spare. It only needed one truck to jump the road when passing the box and the men inside would have been `goners’. Still, throughout Ivor’s years on the railway, he told me that nothing untoward had ever happened at this spot.

Gas Ferry crossing proved difficult in other ways in that, with this type of yard, trains had to be kept on the far side of the crossing on the Down road until room could be made for the trains from Temple Meads to pull into the yard itself. An additional problem was that since Canon’s Marsh was a mileage yard where wagons were loaded, sheeters on the day turns were always sheeting loaded wagons. These men carried the sheets on their heads and with them they climbed up ladders on to the top of wagons. Drivers always had to be on the look-out for these sheeters when shunting. Other obstacles were the horses with their carts drawn up against the wagons. Going out on to the dockside, a shunter always walked in front of an engine to stop any traffic coming along the road which led from the city centre. Mention of the docks leads us on to another interesting aspect of traffic working at Canon’s Marsh. At the time Ivor knew the branch, Class 15XX, 17XX and 20XX tank engines were using the yard, their lightweight also allowing them to go out on to the quayside. However, their lightweight was also a serious disadvantage since they slipped so much when shunting the yard.

Being very near the edge of the dock, there was always danger from so many obstacles all around. There were ropes from cargo ships, items such as boxes fouling the railway tracks and, on many occasions, it took quite a time to shunt the network of tracks around the docks.

The late Mr W. A. Jupp, pictured with his shunting crew at Canon’s Marsh on 25th July 1935. In the distance Brandon Hill and Cabot Tower can be seen.

Paul Holley

Sadly, one of the old foremen was killed stepping over one such rope leading from one of the ships, moored at the quay. This rope was looped over one of the bollards which are always to be found on the docks and when the ship moved slightly, the rope, being a little slack, tightened, came up and caught the man. The injury he received cost him his life.

Another similar incident occurred one night when shunting was taking place along Gas Lane. A Polish seaman, coming from his ship, saw a row of wagons stop on the crossing. He started to crawl under the wagons just as the shunter called the engine back. Unfortunately the seaman’s legs were severed. A young shunter held the pressure points on the man’s legs until the ambulance came, and then he returned to his work. Ivor feels that the shunter should have been shown some appreciation from the G W R, but this did not happen. This shunter is now deceased, but Ivor reckons he was the sort of person that he will always remember.

It was almost impossible to avoid this type of accident when shunting, for it was obvious that the crossing keeper, or the shunter, could only be on one side of the rake of wagons at any one time. This could easily lead to trouble, particularly when seamen came back from a night out, some of them a little the worse for drink! Often they would take chances just as the Polish seaman had done.

Working a transfer freight which, in Ivor’s days, was generally worked by 0-6-Os of the 23XX, 24XX and 25XX series, from Temple Meads into Canon’s Marsh, had its interesting side. Once across the Basin Swing Bridge, the freights passed along the backs of shops, the latter’s fronts facing out on to the Hotwells Road. Roughly between every five shops there was an entrance way from the shops out on to the railway tracks, and more than once collisions occurred between trains using the line and cars and lorries.

WORKING AT CANON’S MARSH ON SUNDAYS – In accordance with an undertaking given by the British Transport Commission, no train or engine must run between Lower College Green Avenue and the road known as the `Butts’; nor must any shunting or moving of any train or wagons be carried out during the hours of service at the Cathedral on Sundays in a manner which is likely to be audible in the Cathedral.

No sounding of the whistle of any engine between the points shewn above must take place during the hours of service in the Cathedral on Sundays.

Having talked a little about freight working on the Canon’s Marsh let us now take a trip on the line. We have already seen how the 15XX, 17XX and 20XX classes were commonly used on the line. The 17XX and the 20XX had their rear sand boxes on the footplate and this was a real nuisance for the firemen who had to prepare them. They often skinned their knuckles when filling the boxes with sand or when they were firing the locomotives. These engines were stabled at St. Phillip’s Marsh and drivers were allowed 45 minutes to prepare them for the road. One of the turns Ivor worked to Canon’s Marsh Goods Yard was as follows:

He used to book on duty at 6.15p.m. and departure `off shed’ was roughly 45 minutes later at 7.00p.m. During this time the engineman did any oiling required, filled the lubricator, examined the engine for any defects and tried both vacuum and steam brakes. The fireman prepared the fire until he had a good head o steam, examined the smokebox and ensured that the smokebox door was screwed up tight. He also tried the sanding equipment, front and rear, and checked that they both delivered sand right down on to the rail. He topped up the sand boxes when empty, trimmed the headlamps and ensured that the rear lamp was complete with its red shade. With the help of the driver, he filled the tank with water and then, when all was done, the footplate crew were ready to leave the shed which, in Ivor’s case, was generally around 7.00p.m. Leaving the shed, bunker first, locomotive and crew travelled, via the loop line at St. Phillip’s Marsh, out under Bath Road Bridge, down through Bedminster, on to Malago and then to Parson Street box and over the branch to Ashton Junction box. Taking the Wapping and Canon’s Marsh line we would head up toward Swing Bridge South box, would cross the Swing Bridge itself, arriving at Ashton Swing Bridge North signal box. Trains for Wapping would pick up the single line staff here, although it was double track for us to Canon’s Marsh!

From Ashton Swing Bridge North box we continued on to Avon Crescent Crossing, where the signal box operated the road gates and also the signal for the Swing Bridge over the Basin. Once over the bridge the train squealed round the curve past Merchants’ Dock, on again past Pooles Wharf, until we finally reached the black and white banner signal protecting Gas Ferry Road crossing and the yard at Canon’s Marsh. Once the signal was in the `off’ position we went into the yard, but not before we had received an additional signal, by hand, from the crossing keeper. We arrived at the yard around 7.45p.m. the timing depending on whether the Swing Bridge was open for rail traffic. The pilot, until our arrival, shunting the yard, would then couple on to the front of the train it had been forming and leave the yard as the 8.00p.m. transfer freight to West Depot. Once the train was put off at West Depot, men and engine went off to shed, again via the loop at St. Phillip’s Marsh. It was very rare to go to shed through Temple Meads.

Having seen the journey Down, let us quickly catch the 8.00p.m. transfer back. This train ran all week except Saturdays. It was worked by the pilot engine which had been shunting all day at Canon’s Marsh. As soon as the relief pilot engine arrived in the yard, at around 7.45p.m., the pilot went on to the train it had already formed, which, incidentally, was usually made up of wagons carrying mixed traffic. The guard would come up, give details of the load and take the name of the driver and the number of the engine. With the banner signal in the `off’ position and, at night, the green light from the crossing keeper, you gave a touch on the whistle and started to move out of the yard. When you felt you had a tight chain on the couplings and saw the guard’s van moving off, (at night the guard would wave his lamp when this happened), you could touch the whistle to acknowledge this. As you left the yard the Floating Harbour would soon come into view on your left. Lying alongside the quay was the training ship Flying Fox and as you approached it you could often see cars, owned by the officers on board, fouling the Down road. Stopping the train you would walk aboard and inform those in charge that they would have to come and move them. Once this had been done and you had received the signal from the guard, you would be clear to set off again. You had to be always on the look-out along this stretch to make sure all your train was on the move and in one piece, for the youngsters around this area of Hotwells would sometimes slip between the wagons and uncouple them. A guard would often see his train disappearing into the distance after it had been delayed for some reason. The regular guards who worked these transfer freights knew when the Swing Bridge would be swung and how long it would take to get into Canon’s Marsh. While waiting for the bridge to move back for rail traffic, they would slip around the corner to their favourite drinking house, have a quick one and then quickly get back into their van. After all, if by the time they returned from the pub their train had gone, it was only a short walk to the yard at Canon’s Marsh!

The section of the line between Ashton Swing Bridge North and Canon’s Marsh was always full of incidents, and something was always going on. There was the traffic along Hotwells Road, the ships berthed on the Floating Harbour, while across the Harbour was Heals Dockyard and, as you passed by, your attention was sometimes distracted by the launching of some ship. This line was truly part of old Bristol. It reminded Ivor of the old tram days. It had so much character and it is sad to think that it is now only a memory. Ivor’s final comment was, that in those days, a railwayman’s life was very demanding and he worked all the hours that God sent. However, like many other railwaymen I have talked to, Ivor gave me the impression that he enjoyed the work, that time passed quickly and that he would be quite happy to see those days again.

Ronald Gardner, whose name cropped up in the previous chapter, worked the lines to Portishead and Bristol City Docks from 1936 until the cessation of steam from St. Phillip’s Marsh shed in the early 1960s. I’ll let him reflect on some of the events and places mentioned earlier in the text.

`A fairly typical day would begin at 7.05a.m. when we would book on duty at St. Phillip’s Marsh shed. In the early days we would prepare engine No. 1538, while from the 1940s onwards, the chances would be that we would have a member of the 22XX or 36XX classes. In the 1950s, engines of the 94XX class were allowed to work to Portishead and over the Wapping Wharf line. They were subsequently allowed to work the Canon’s Marsh road.’

`Off shed by about 7.50 a.m. we would then run light engine to West Depot Up side. Here we would pick up our goods train and this we would propel from the yard towards South Liberty Junction signal box. Then, making our way to West Loop North Junction, we would travel on through Ashton Junction to Clifton Bridge, Oakwood, Pill, Portbury Shipyard loop, Portbury Station and on down to Portishead. Here we shunted the yard as required, the usual traffic being coal, timber and, from the 1950s onwards, phosphorus. Once the shunting was over the engine was turned on the turntable adjacent to the old power station, Portishead `A’. We then had a cup of tea and at about 12.20 p.m. our reliefs came on duty and we worked a passenger train back at 1.34p.m. Our arrival at Temple Meads was 2.05p.m. Here we were relieved, walking back to St. Phillip’s Marsh to book off duty at around 3.05p.m.’.

`A couple of points to note here, the first being in connection with the turntable at Portishead. It was of a rather different design to that to which I was accustomed on the GWR. It was large enough to take a 22XX or a 23XX standard goods engine and you actually went round with the table, since the turning mechanism was operated from the table itself. As mentioned previously, once we had shunted the yard we worked the 1.34p.m. passenger back to Bristol. The engine for this turn was usually a Class 55XX 2-6-2T and it was often my luck to get engine No. 5577! This was always my favourite (!) since it was a locomotive that never steamed freely. Unfortunately, I seemed to have more than my fair share of this engine. Other locomotives I can remember working the line included Nos. 5512, 5535, 5547, 5548 and 5561. Sometimes we would get engines of the 37XX or 46XX classes, depending upon the general availability of the locomotives on shed.’

`As far as the personalities, I can still remember some of the shunting staff then at Portishead. People like `Tot’ Callard and Ron Hayman, while the refreshment rooms on the station platform were, of course, run by Mr & Mrs Howe. It was very easy to remember her; she was lovely, with golden plaited hair, lovely skin and very good looks, all the locomotive men will tell you the same. Still, I had better move on, I think! The chaps in the signal boxes, and the shunters helped to make their job so enjoyable, and memories of driver, fireman, guard and shunter having a quiet five minute nap, before leaving Portishead around midnight on a late freight or light engine, still come to mind.’

There would sometimes be operating problems on the line but these were rarely serious and were due, mainly, to the single line working which, of course, involved having to wait for trains at the various crossing points, such as Pill. Occasionally, some delay was caused by the felling of trees in Leigh Woods, between Clifton Bridge and Oakwood loop, while at other times problems were sometimes encountered with the very wet rails in Pill Tunnel. All were fairly minor in nature!’

`On the traffic side, I think it should be mentioned that the Portishead, Wapping Wharf and Canon’s Marsh lines were feeders to the former marshalling yards at West Depot, Temple Meads and Stoke Gifford. For example, the 3.05p.m. train from Portishead conveyed traffic for Albright & Wilson of Birmingham. This was conveyed to Stoke Gifford yard for the 11.20p.m. Stoke Gifford and Oxley sidings freight. Also it must not be forgotten that the Saturdays only transfer from Canon’s Marsh conveyed traffic to West Depot for the 10.55p.m. West Depot and Plymouth (Laira) while the 7.20p.m. transfer from Temple Meads to West Depot contained certain traffics for Plymouth, Taunton, Exeter and Barnstaple. There was also a transfer from Temple Meads at 8.45p.m. to West Depot for the 10.55p.m. West Depot and Barnstaple. This conveyed an occasional wagon for Taunton. In addition, there was also a transfer at 8.lOp.m., Stoke Gifford to West Depot, for traffic to Taunton, 11.45p.m. and Exeter, 2.30 a.m. Another late night transfer was the 11.lOp.m. West Depot, Wapping, Temple Meads and Stoke Gifford, this conveyed traffic for Gloucester and Worcester. Finally, in the period from the 1930s to 1948, another transfer would start from Ashton Meadows at 11.30p.m. This conveyed coal empties to Pengam sidings, Cardiff!’

`On the Canon’s Marsh line it was very common for trains to be stopped on several occasions, due to the swing bridge being in operation or when people left cars fouling the line in the proximity of the R N V R ship Flying Fox and, of course, it needed action on the part of the engine crews to remove the offenders. Other problems often arose when crews were shunting the private sidings, due to the number of public footpaths crossing the line at various places including those at Heber Denty’s timber siding and at Osborne & Wallis’ coal siding.’

Also along this stretch, an incident of special note occurred around 1937. Number 5 transfer was leaving Canon’s Marsh around 8.30a.m., engine and van, for Ashton Meadows and the engine, a Class 23XX, was travelling tender first. As was the usual procedure, the fireman had made a cup of tea and both he and the driver were trying to snatch a bite to eat, breakfast having been fried on the shovel, as was the custom in those days! At a point some half-way along Hotwells Road, a lorry pulled across the rails and started to unload its cargo of beer on to P. & A. Campbell’s pleasure steamer Glen Usk, which was tied up alongside the harbour wall. What happened next was unbelievable in that neither driver nor fireman saw the lorry, belonging to D. M. W. Bullock Limited of Canon’s Marsh, bottlers of Bass etc!, and before any evasive action could be taken, the lorry and its contents were pushed into the Floating Harbour. A subsequent enquiry into the accident, not surprisingly, laid a considerable amount of blame on the driver. Fortunately, no lives were lost.’

`As a young fireman, I was working at Canon’s Marsh on the evening turn one very dark, winter night. It had been pouring with rain for several hours when, walking along Anchor Road I saw three of the ladies of `easy virtue’ who were always much in evidence in those days in the dock area. Of course, if there were no ships in port there was `no work’ and times were hard! This particular night, these three laides were soaked to the skin due to the heavy rain, and I remember the keeper at Gas Ferry Crossing telling them to go a little way down towards the gasworks and there they would find a nice fire in the watchman’s hut so that they could dry their clothes. You can imagine the railwaymen’s curiosity to walk down to the watchman’s hut and see three ladies as naked as the day they were born! You can just picture the amusement this caused to the half a dozen men who were on duty at the time!’